Understanding Japanese Imperialism

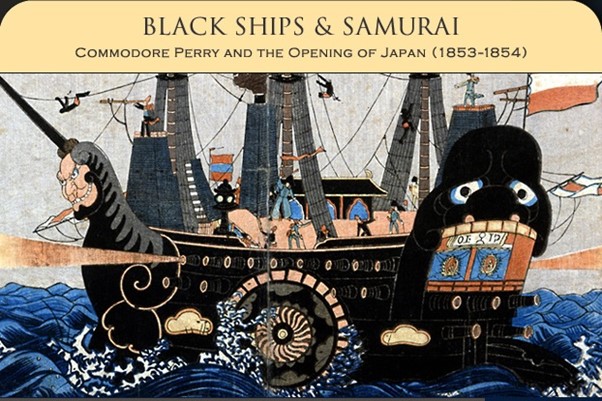

Figure 1: MIT, 2010

Thanks to Janine Fedorchuk-Weeks (2022 teacher accompanying the tour) for this great piece on Japanese Imperialism.

Empire-Building

Understanding Japan’s aggressive imperialism in the lead-up to the World War II can be mind-boggling if we begin with the bombing of Darwin in 1942, so please allow me to review a bit of pre-war history before we embark on our adventures together in October.

In Year 9 history, you may recall learning about the main causes of World War I: militarism, alliances, imperialism, and nationalism. One of the historical concepts we like to study is change and continuity. In a comparison of the causes of World War I and the conflict in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, we can understand that some things changed but a lot remained the same.

Japan’s imperialist ambitions put the world on edge a long time before the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941. As many students of history may remark that it was not altogether a surprise that Germany invaded Belgium in 1914 due to the tense situation in Europe, one could also conclude Japan’s attack on places like Pearl Harbour and Darwin in WWII were not a surprise either.

In the period after Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s ‘opening of Japan’ on the orders of American President Millard Filmore in 1853, Japan experienced an intense period of increased imperialism, ultranationalism, and militarism. Check out the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Black Ships & Samurai unit of their Visualising Cultures webpage at: MIT Visualizing Cultures for historical images of this significant event and an analysis by historian John Dower (figure 1 above).

As feudal Japan woke up to the realisation that global changes, mainly the nature of European imperialism, were leaving Japan vulnerable and powerless in the newly emerging balance of power, Japanese society opened its doors and a hunger for interaction with the world replaced two centuries of isolationism. Japanese leaders were quick understudies who learned the rules of empire building from their mentors. A French political cartoon from 1898, China- The Cake of Kings… and of Emperors, (figure 2).

A French political cartoon from 1898, China- The Cake of Kings… and of Emperors, (figure 2) paints a picture of this dynamic very clearly for us.

(Figure 2: Le Petite Journal, 1898)

This dynamic also explains Japan’s participation in World War I on the side of the Allied powers, a fact that usually bewilders my Year 9 history students.

Historian Takashi Fujitani (1998) analysed the transformation of ceremony and pageantry during the Meiji Restoration when Emperor rule replaced the feudal shogunate system in his book Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan. He highlights the mimicking of European pageantry as Japan sought to consolidate its own piece of empire. What elements of European culture do you see represented in the woodblock print pictured below (figure 3)? Similar woodblock prints by Chikanobu are dated in the 1890s. These symbols of power and statesmanship are very different to what you would have seen just a few decades earlier in feudal Japan. The pace of change for Japan after Commodore Perry’s arrival in 1853 was rapid.

(Figure 3: Chikanobu, 1838-1912)

Another aspect of Japan’s imperialism that should not be ignored is ultranationalism and a concept of Japanese Pan-Asianism because it wasn’t just about territorial expansion and colonial acquisition. I really cannot explain Pan-Asianism better than Professor Rana Mitter so check out his succinct (less than 2 minutes) explanation here: Japanese Pan-Asianism: An Introduction | Facing History and Ourselves. What changed? The emergence of Japanese beliefs about racial and ethnic superiority similar to that of Nazi Germany. What remained the same? Justifications for a Western style of imperialism which led to ruthless brutality across China and Southeast Asia as Japan attempted to establish colonies under its military rule. In quick summary, Japanese imperialism was driven by a sense of Japan as a leading race (shidō minzoku) who were benevolent in their creation of a unified Asian region, called the Co-Prosperity Sphere, in response to existential threat from European powers (Dower, 1993, p. 203).

Japan’s version of fascism was extreme as it was underpinned by cultural values which hold the pursuit of perfection (kodowari) in high regard, no matter the size of the undertaking. In Japanese culture, settling for half-measures is frowned upon, good enough isn’t good enough.

Kodowari is great when we are talking about things such as folding origami, actors pretending to be samurai while collecting rubbish on city streets (figure 4), academics, training to become an elite athlete, or the craftsman’s spirit (shokunin kishitsu) but not so great when we are talking about using military power to dominate and control other groups of people. In a wartime context, this cultural value played out in many terrifying ways for those opposed to Japanese empire. This dedication to kodowari might explain some aspects of the heavy-handed bombing of Darwin. The attack on Darwin was led by Commander Mitsuo Fuchida of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service who had also led the first wave of air attacks at Pearl Harbour.

(Figure 4: Wen 2022)

‘[Fuchida] compared it with an earlier attack on Rabaul and said: “It seemed hardly worthy of us. If ever a sledgehammer was used to crack an egg it was then.”

Yet those of us in Darwin on February 19, 1942 were left in no doubt that once Fuchida was given a task he was extremely thorough in its execution, where or not his hear was entirely in it.’ (Lockwood, 2005, p. 4)

In the late 1800s, Western civilisation looked upon Japan’s emergence with approval but there were limits to the flattery. ‘Westerners, far from condemning the Japanese for their aggressions, applauded them as being apt pupils. They also taught the Japanese how ruthless the game of imperialism could be and how unwilling Westerners were to accept other races as full equals’ (Reischauer cited in Facing History, 2022). By the time the two sides faced off in the Pacific Theatre there was already a complicated history which cannot be explained by a simplistic view of territorial expansion.

References

Chikanobu, 1838-1912. Leaving the Imperial Palace. [online] Available at < Fuji Arts Japanese Prints - Leaving the Imperial Palace by Chikanobu (1838 - 1912)> [Accessed 20 July 2022].

Dower, 1993. War Without Mercy. 7th edn. United States of America. Pantheon Books.

Facing History, 2022. Japanese Imperialism and the Road to War. Available at: <Lesson: Japanese Imperialism and the Road to War | Facing History> [Accessed 20 July 2022].

Facing History, 2022. Japanese Pan-Asianism: An Introduction. [video] Available at: <https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/video/japanese-pan-asianism-introduction> [Accessed 20 July 2022].

Fujitani, 1998. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan. 2nd edn. Berkley, CA. University of California Press.

Le Petite Journal, 1898. China- the cake of kings and… of emperors. [online] Available at: https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/image/imperialism-cartoon-1898 [Accessed 20 July 2022].

Lockwood, 2005. Australia Under Attack: The Bombing of Darwin 1942. Australia. New Holland Publishers.

MIT Visualizing Cultures, 2010. [online] visualizingcultures.mit.edu. Available at: https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/black_ships_and_samurai/index.html [Accessed 20 July 2022].

Wen, L. Samurai Trash Collectors Defend Japan’s Street Cleanliness With Dramatic Litter-Picking Antics. [online] thesmartlocal.com. Available at: https://thesmartlocal.com/japan/samurai-trash-collectors/ [Accessed 22 July 2022].

Comments

Post a Comment